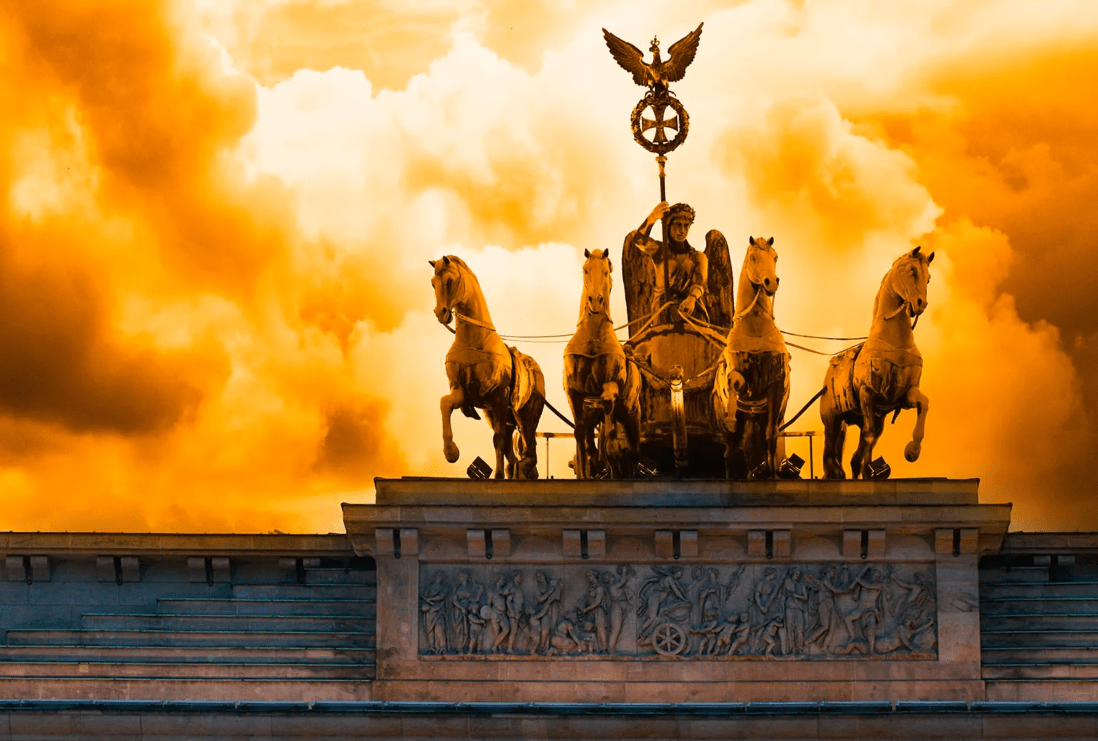

When William I was crowned Emperor in 1871, it was the beginning of a new heyday for Germany.

Everyone has the same physical shape, as far as this is possible in such a large number of people: grief, blue eyes, red-blond hair, heavily built bodies, but strong when it comes to attacking. With regard to work and effort, they do not have the same endurance due to climate and soil.

Germans between bars and roofs

For the Romans, the “Germans” were a gathering term for all who lived east of the grilles – the Celtic-speaking peoples of present-day France – and west of the roofs and steppe nomads west of Southeastern Europe.

Well to note, it is not at all certain that all Germans spoke what we today call Germanic languages. They felt no connection – all ideas of a common Germanic ethnicity stem from the 19th century of Romanticism and Nationalism.

By contrast, they had plenty of minor ethnic groups, or gentes , as the Romans called them. We usually translate the Latin word with “tribes”, but that is misleading. The differences between different gentes were great. Sometimes it was about large peoples’ associations, such as the late Ancient Franks and the Alemans. In other cases, gentes were small and geographically limited groupings.

Battled the Romans at the Teutoburg Forest

During the decades surrounding the birth of Christ, it seemed as if much of Germany was to be incorporated into the Roman Empire. After the defeat of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD, however, Emperor Augustus contented himself with holding on to the land south and west of the Rhine and Danube.

Cities such as Cologne, Trier, Mainz and Regensburg were founded by the Romans. Today, southern and western Germany has plenty of Roman cultural heritage, with Porta Nigra in Trier as a prominent example.

At times, charismatic warlords succeeded in creating supremacy in the free Germania, but they never developed into permanent kingdoms. Arminius, the conqueror of the Teutoburg Forest, created such an empire, but it collapsed at his death in 19.

As a rule, the relations between the Romans and the free gentes were good, and many Germanic soldiers were recruited into the Roman arm. It happened that Romans and Germans clashed in armed conflicts – for example, the Markers War in 166-180 – and that Germanic armies hardened the empire’s land. But the emperor’s provincial governors mostly managed to hold the positions.

The Roman Empire weakened

In the 400’s, the Roman Empire weakened in Western Europe. In this situation, Germanic warlords took over the defense of several provinces, while other gentiles used the situation to plunder. The Ostrogoths and the Langobards built up the kingdoms in Italy, the Visigoths in Spain, the Vandals in North Africa, the Franks in Gaul and the Anglo-Saxons in Britain.

The epoch has gone to history as a time of migration, but it is doubtful if it was always about real people on a hike. In many cases, it was rather army relocations, and many field lords acknowledged the emperor’s supremacy.

Talking about “Germanic” migrations leads wrongly, as other groups – Celtic, Iranian, Slavic, etc. – also participated.

In today’s Poland and the Czech Republic, which was largely populated by German-speaking people during antiquity, slaves now settled.

Most of the area corresponding to present-day Germany was ruled in the 500’s, 600’s and 700’s by small kingdoms and dukes, whose names are repeated in the present landscapes.

The duchy of the Bajuvar was the origin of Bavaria, the kingdom of the Thilrings to the Thilringen, the empire of the Saxons to Lower Saxony, and so on.

Karl the Great Emperor

Most powerful was the kingdom of the Franks, which included today’s France and Belgium as well as a large area east of the Rhine. The expansion of the Franks culminated in the late 700’s, when Karl the Great subdued all Germans and crowned the successes of proclaiming himself Roman emperor in 800.

The Franks followed missionaries, bishops and monastic founders. In the 7th and 8th centuries, the area east of the Rhine became solidly Christian, with an ecclesiastical infrastructure of cathedrals and monasteries that have characterized the cultural landscape into modern times.

Christian culture became a lasting legacy of the era, but the empire of Karl the Great became short-lived. Already in the 8th century it was divided into smaller kingdoms. The eastern parts, the “East Frankish Empire”, were a weak kingdom in which the king had limited influence and power, however rest of the area were controlled by dukes.

In the year 900, there was not much at hand that the East Frankish empire would develop into a great power and that its people would re-orient Europe’s history. But that’s exactly what happened.

The Magyars plundered in the East Frankish kingdom

An important reason why Germany became a medieval great power was the need to guard against an external threat. The Magyars, today’s Hungarians, settled in the late 800’s on the Eastern European plains where their descendants still live.

They went on looting trains throughout Central Europe and the East Frankish Empire was hit hard. The only way to offer effective resistance was to join a military force.

Duke Henry of Saxony, who was elected king in 919, used the threat as an argument to build an increasingly powerful monarchy. He also used his position to annex the neighboring kingdom of Lotharingia, giving the kingdom a boundary that was considerably further west than the present one. Medieval Germany comprised most of the Benelux area and a good portion of today’s eastern France.

Otto the Great and German-Roman Empire

After Henry’s death in 936, politics was pursued by his son Otto I (Otto the Great, dead 973). By relying on loyal bishops as civil servants and appointing royal agents, palace tombs, to properties around the country, Otto strengthened his authority over the belligerent dukes.

In the Battle of Lechfeld in 955 he basically defeated the Magyars. But Otto’s ambitions were greater than that. Like his father, he expanded toward the slaves to the east on the other side of the Elbe and Saale rivers.

His campaign to Italy resulted in him being hailed as an Italian king and in 962 crowned Emperor of the Pope. This event is considered the starting point for the “German-Roman Empire”, also known as the Holy Roman Empire by the German nation.

German History and War

During the century following the emperor’s reign, Otto’s successor continued his policy with vigor. While France disintegrated in the independent nobility and Anglo-Saxons and Vikings fought over England, Germany became a great power.

It was also during this time that terms such as “Germans” and the German Empire “broke through. (The word “German”, in Old German diutisc , really means “one who speaks the vernacular”, as opposed to Latin.)

Expanding German-Roman Empire

The boundaries were extended to all stretches of weather, from Central Italy in the south to Holstein in the north. In the southeast, today’s Austria and Slovenia were integrated with Germany. In the 1030s, the empire also expanded in the Southwest, where the great Burgundian kingdom from Franche-Comte to Provence was incorporated through a personnel union. Rhône became the emperor’s border river to the west.

Germany War History

In the 1100s and 1200s, expansion continued eastward, in Pomerania and Silesia. The Czech kingdom, which at the same time stabilized with Prague as a center, became part of the empire.

Rise of German Language

In the wake of the political triumphs, an economic upswing followed. German colonizers, both gentlemen and ordinary peasants, sought east, where they founded villages, opened mines, and cleared land. As a result, the language boundary was postponed, so that German became the dominant language in several districts that are today outside Germany itself.

The Hanseatic cities were grown

On the Baltic Sea coast, a pearl band of German merchant and craft communities grew up. These cities – Lubeck, Hamburg, Wismar, Rostock, Stralsund, Danzig, Königsberg, Riga, Reval (Tallinn), Visby and others – became hubs in Hansan, the German merchant organization that dominated Northern Europe’s mercantile life from the 13th century to the 1500’s.

The strongest was the German expansion between Elbe and Oder, in what is today considered East Germany. Here, in principle, the entire population was Germanized, with the exception of a Slavic (Sorbian) peoples still living at Cottbus and Bautzen.

Germany History Facts

Often the Slav princes chose to embrace German culture and German language, after which they continued to rule over their respective territories. The Obotritic prince’s house remained ruler of Mecklenburg until 1918.

However, the most important of the empires established east of Elbe was the entirely German land county of Brandenburg, with Berlin – founded around 1230 – as its capital.

The Pope banned Henry IV

The German-Roman Empire was not without worries. Because the emperors based much of their control of Germany on the network of bishops, there was a serious threat when Pope Gregory VII objected that worldly princes gave bishops investment, that is, inaugurate them to office. The Church would rule itself without interference from outside, said the Pope, who banned and deposed Emperor Henry IV when in 1076 he took the opposite position.

The curse struck hard. With the Pope releasing all German princes from their oath of allegiance to Henry, it was free to revolt. Henrik resigned to the Pope’s demands and traveled the following year in remand to the Pope’s residence in the Italian castle of Canossa. Gregory then abolished the ban, which made it easier for Henrik to fight the rebellion.

Then he struck back against the Pope with full force. Gregory was expelled from Rome and died in exile.

The dispute between the emperor and the pope had come to a halt, let alone the specific problem of the bishopric appointments (the investiture battle) was solved by a compromise in 1122. But there were bigger dilemmas.

Brief History of Germany

Fredrik I Barbarossa

As the peoples of Europe increased, cities grew and political life became complicated, the emperors were forced to pursue a tough and warlike policy to maintain their empire. The most famous of all German-Roman emperors, Fredrik I Barbarossa, who ruled between 1152 and 1190, must travel back and forth across the Alps with ever-new armies to fight his numerous opponents in Germany and Italy.

The last of the great German-Roman emperors, Frederick II, which was crowned in 1220, also inherited the Kingdom of Sicily and was in fact more Sicilian than German. He prioritized his Italian possessions and entrusted the government of Germany to local forces.

The disintegration of the German-Roman Empire

This was perhaps a good temporary solution to an increasingly difficult government problem, but it had a devastating consequence after Fredrik’s death in 1250. His family, the house Hohenstaufen, lost the German throne in 1254, was haunted by long-standing throne battles.

When the Germans again in 1273 accepted a common king – the South German prince Rudolf of Habsburg – the empire had broken down in autonomous dukes, land counties and city states.

In the late Middle Ages, the divide accelerated, so that in the 16th century Germany consisted of thousands of kingdoms – some thirty larger worldly dominions, over ninety ecclesiastical, more than one hundred counties and an inexplicable amount of self-governing knightly empires, cities and peasant republics.

In the Rhineland and southern Germany, many kingdoms consisted only of a castle and the nearest square kilometers around it.

Winged Emperor

In a law of 1356, “The Golden Bull,” established a preexisting practice, which meant that seven princes, so-called kurfursts, had the right to choose emperors. It involved four worldly princes and three ecclesiastics: the duke of Saxony, the tomb of Brandenburg, the tomb of the Rhine, the Czech king of Prague and the archbishops of Mainz, Trier and Cologne.

But it was a winged imperial power. From now on, the emperor’s influence was limited to his own heritage countries. Rudolf of Habsburg and his descendants controlled Austria, which remained the family’s territorial base until the First World War.

Habsburg, Wittelsbach and Luxembourg

Among the most dangerous power rivals in the Habsburgs were the house Wittelsbach, which ruled Bavaria, and the house Luxembourg, which in the 1300’s built a regional great power with its center in Bohemia.

In the 13th and 14th centuries, these three dynasties fought for the emperor’s office, but because the emperor was elected by election and the chief priests usually chose a weak candidate – that is, a man who could not make life difficult for themselves, it was difficult for one and the same family to keep the emperor crown for a longer time.

When we look at the chaotic political map of late medieval Germany, it is easy to lose faith that the country even existed as a political entity. But then we make mistakes. The Germans of that time were well aware of the kingdom’s existence. In times of turmoil that required joint efforts, chiefs, knights and other rulers gathered in congregations to confront common problems. The result was a Reichstag (“Parliament”), whose powers gradually increased in the 15th century.

The thirty-year war

Thus, Germany being politically divided was not necessarily the same as being weak. But the kingdom had an Achilles heel. When the early modern states grew up in Western Europe in the 16th centuries, Germany became militarily vulnerable. No joint German army existed. The German princes’ efforts to create their own states were at odds with the emperor’s ambition to rebuild a stable empire.

This conflict scenario led to one of the greatest tragedies in Germany’s history, the thirty-year war that devastated the country between 1618 and 1648. In German history writing the war is associated with a devastation that can only be compared with poet death and the world war of the 20th century.

Powerful habsburgs

By this time, the Habsburg house had held the emperor’s throne for two centuries, ever since 1438. Through a skilful marital policy, the Habsburgs had embraced large territories and kingdoms – the present Benelux region, Spain, the Czech Republic, large parts of Italy, and more – and extended their empire throughout globe.

The conquistador’s conquests in America had given them wealth, not least silver. The most powerful Habsburg, Emperor Karl V, dominated the whole of Western, Southern and Central Europe between 1519 and 1556.

It goes without saying that such a position of power does trouble enemies. Many felt threatened. The French kings, wedged between the Habsburgs of Spain, Germany and Italy, were happy to ally themselves with German princes who feared the Habsburg house.

Protestant princes

A recurring cause of conflict was religion, as Germany came to divide between Protestant and Catholic princes. When the Habsburgs were closely allied with the papacy, many German princes chose to become Protestants and strengthen their own principality by taking control of church property. To oppose Catholicism was to counteract the growing power of the Habsburgs.

The igniting spark of the Thirty Years War was an acute conflict in 1618 between the Habsburg emperor in Vienna and his largely Protestant subjects in Bohemia. Soon all of Germany had been drawn into the war.

The neighboring countries – Denmark, Sweden, the Netherlands, France, Transylvania, and others – also participated, with which the warring forces recruited soldiers from countries that had nothing to do with the conflict, such as Scotland and Croatia.

Researchers have estimated that forty percent of the German rural population and about one-third of the city’s population died as a result of the war, mainly from famine and disease that followed in the wake of the army.

Westphalian peace

The Thirty Years War ended in the Osnabrück and Münster Peace in 1648 (Westphalian Peace). For the German-Roman Empire, peace was a humiliation. Both Sweden and France made land gains in German territory. The emperor was forced to admit that the Netherlands and Switzerland were independent and were no longer part of Germany. Every single German prince was granted full sovereignty.

In practice, this meant that Germany had ceased to exist. Add to that the decline in population and the predictable decline in trade and business that the war brought, and the country’s situation could hardly get worse.

For more than two centuries now the history of Germany was a story of its independent principality. Some were significantly stronger than the others, but none were powerful enough to unite the country.

Germany Facts

Habsburg against Prussia

In the southeast, the Habsburg emperor’s house created a Central European great power that in the 18th century also included Hungary, Croatia and Transylvania. In the northeast, the Kurfursterns of Brandenburg built a militaristic state, the Kingdom of Prussia, which covered large areas of present-day Poland. There was often enmity between these two kingdoms.

There were more actors on stage. The rulers of Hannover succeeded in 1714 to ascend to the throne in London, after which their north-west German principality for over a hundred years was united in a personal union with Britain. During much of the 18th century, the Saxon Kurfursten were kings of Poland. Lantgreve Fredrik of Hessen-Kassel was king of Sweden between 1720 and 1751. And so on – the personal strategies of the princes made it impossible to even imagine a united Germany.

The German-Roman Empire was abolished in 1806

This led to new bloody tragedies and humiliating occupations during the conflicts that followed the French Revolution. Between 1792 and 1815, there was rarely peace in Europe. French, Austrian, Prussian and Russian armies marched across Germany, and on Napoleon’s orders the political map was repeatedly drawn.

In 1806, the Habsburgs took the logical consequence of the development and even formally abolished the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation. They contented themselves with being only emperor of Austria.

German nationalism

At the same time that political Germany reached the low-water mark of humiliation, a seed was sown for radical renewal. German nationalism saw the light of day. In fact, these were two phenomena that crucified each other, one political and one intellectual.

First, the defeats against Napoleon’s French armed forces forced Prussia and Austria to carry out military and administrative reforms. At the Vienna Congress of 1814-15, where Napoleon’s final defeat was confirmed, both of these states emerged victorious.

German Confederation

Many princes, however, perceived nationalism as a threat to themselves. There was no mention of restoring a German-Roman empire. Instead, at the Vienna Congress, the German Confederation was formed, a loose organization with some forty members. In practice, each state remained independent.

Nationalism was fueled by the liberal currents that swept across Europe in the 1820s and 1830s. During the year of the revolution of 1848, when Europe’s royal house was threatened by liberal revolutionaries above all, for a time it looked as if a united Germany would be proclaimed on a Bundestag (Riksdag) in Frankfurt am Main.

But the attempt failed, not least because the Prussian king refused to play the role of unifying figure. The German princes remained conservative and did not want to play in the Liberals’ games.

Iron Chancellor Otto von Bismarck

The man who represented Prussia on Bundestag in the 1850s was a conservative landowner named Otto von Bismarck. At first, like the Prussian king, he had only contempt for the liberals and their visions of German unification. But then he changed – not in relation to the middle class liberals, but well when it came to Germany.

By further strengthening Prussia, Germany would unite, not on the terms of the Liberals, but on the Prussian regime. This presupposed that the liberals in their own kingdom were being pushed. Without Prussian agreement, no German agreement. In addition, Austria must be defeated and removed from the new Germany. The Habsburgs were far too strong to accommodate the Bismarck vision.

Blood and iron

The Prussians crushed Austria’s armies, after which the North German principality that fought on the losing side was annexed by Prussia. In the North German League, established in 1867, Prussia was the leading state. The victories on the battlefield caused a large part of the northern German middle class to change sides and pay tribute to Bismarck.

William I Emperor in New Germany

The civil service was completed after France was defeated in 1870-71, a war that led to the French landscapes of Alsace and Lorraine (Alsace and Lorraine) becoming German-owned.

On January 18, 1871, Bismarck paid tribute to the Prussian King William I as emperor of a restored German empire. Otto von Bismarck remained the leader of the united Germany, with the title of Chancellor, for another nineteen years, until the new Emperor Wilhelm II dismissed him in 1890.

As chancellor, he pursued a distinctly peaceful policy, all to make the outside world accept the new, strong Germany. He convened neighboring countries for peace conferences and poured oil on numerous conflict waves.

The German empire thus came, at first, through its very existence to contribute to a peace period of several decades in Europe itself. Outside the continent’s borders, it was different.

Germany had become a great power, and a great power would have colonies. Personally, Bismarck was reluctant to do this, but in the 1880s he was forced to give in to the pressure. In a short period of time, German colonies were established throughout the globe, from rainforests and atolls in the South Sea to vast territories in Cameroon and Tanganyika.

A conservative bastion in Europe

At the turn of the 1900s, Germany was the world’s leading military force, an industrial giant with possessions all over the globe. The many little principalities had been transformed into a kingdom, a Reich . The Germans had become a people under an emperor. But the giant had a night page, and anyone who knows its 20th-century history knows the continuation.

Germany had certainly been united and modernized in agriculture, trade and industry, but politically the country had stopped growing. While liberal and socialist values grew stronger in the legislative assemblies of other European countries, Germany remained in many ways a conservative, undemocratic bastion, a new-age empire that did not follow its time.

German history research mentions that at this time the country entered a special path, a devastating Sonderweg , which would lead to two world wars and demographic disasters that put the Thirty Years War in the shade.